This blog is part of our 2026 Black History Month series. Read more from Natalie Dean and Dr. Lisa Thomas.

This year feels like one of those moments that asks us to pause.

Black History Month is celebrating its 100th anniversary, first established in 1926 by historian Carter G. Woodson. At the same time, the United States is inching closer to its 250th birthday, marking the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. These milestones exist in different timelines, almost alternative universes, but they meet at the same moment—2026.

Those dates matter. Not because of the numbers themselves, but because of what they force us to face.

They ask us to reflect on whose stories we have valued, whose stories we have centered, and what versions of America we continue to pass on to our students. If Black history is American history, are we teaching it that way?

How Black History Month Began—and Why It Still Matters

Black History Month did not begin as a celebration or a themed unit. It began as a correction.

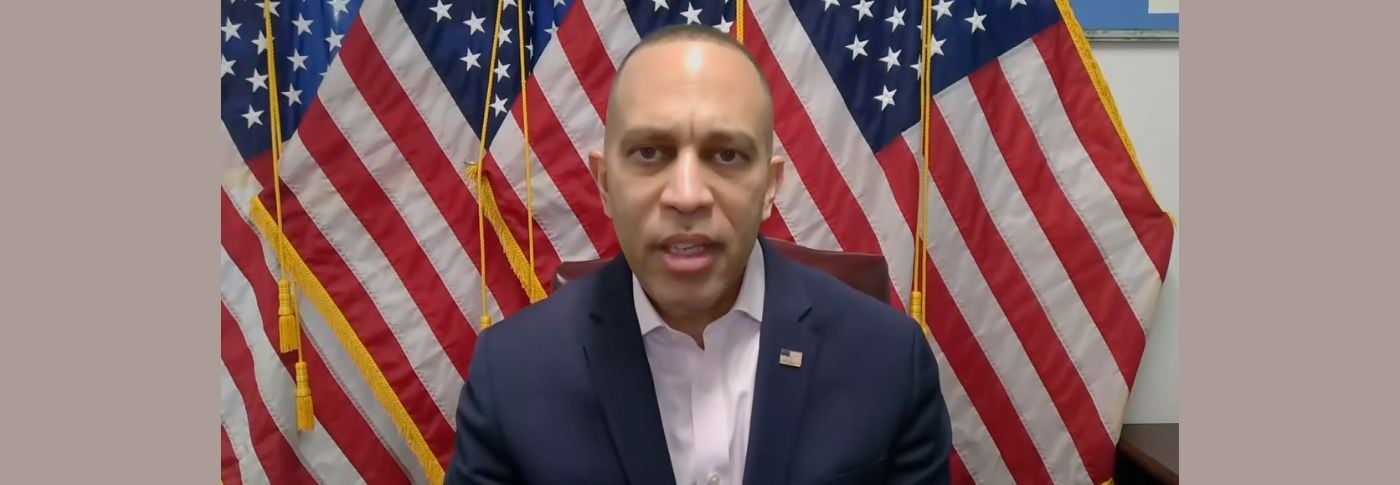

Carter G. Woodson created Negro History Week because he recognized how thoroughly Black people had been excluded from the historical narratives taught in American schools. That exclusion was not accidental—it reflected whose lives were considered worthy of record and whose contributions were pushed to the margins. Learn more from The Man Behind Black History Month.

Woodson’s work was never about separating Black history from American history. His goal was to strengthen America’s understanding of itself by telling the full story. He believed that when students learn a more complete history, they develop a more honest relationship with their country.

A century later, that purpose still matters.

Yet in many schools, Black history is still treated as optional or seasonal. It shows up briefly in February, disconnected from the larger narrative. When that happens, students learn—whether we intend it or not—that Black history is something separate from “real” American history.

Growing Up Loving Learning—but Searching for Myself

I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately, partly because of my students and partly because of my own journey.

I grew up loving to learn. I genuinely enjoyed school. I liked reading, asking questions, and discovering new ideas. Learning felt exciting and meaningful to me.

But as a Black American student, I rarely saw myself reflected in the curriculum in ways that felt whole or affirming.